INCONCRETO NEWS

China’s Grip on Critical Minerals: Can the World Break Free?

The debate around transition minerals is more relevant than ever, with demand surging and expected to triple by 2040. These materials are essential for powering clean energy technologies, including electric vehicle batteries, wind turbines, and solar panels.

Transition minerals undergo a multi-stage transformation before they can be used in battery applications. The process begins with upstream operations, where raw minerals are extracted in resource-rich countries. These materials are then sold to traders or directly to refiners, which handle midstream operations. Refining involves chemical processing to achieve high-purity mineral forms suitable for battery production. In the late midstream stage, these refined materials are used to manufacture key battery components such as cathodes, anodes, and collectors. Finally, downstream actors assemble these components into battery packs for applications like electric vehicles.

In our recent publication, Mining Today, Powering Tomorrow: The Global Race for Transition Minerals, we mapped the key countries extracting crucial metals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, and rare earth elements. As we highlighted, production is highly concentrated: Chile dominates copper extraction, Australia leads in lithium, and the Democratic Republic of Congo is responsible for the majority of global cobalt mining.

As global competition for transition minerals intensifies, resource-rich regions like Greenland are drawing renewed interest. Its vast rare earth deposits, essential for electric vehicles and wind turbines, have positioned Greenland as a strategic asset in securing diversified supply chains. Recent discussions about potential acquisitions and investment opportunities have underscored its geopolitical and economic significance. While the future of such proposals remains uncertain, Greenland’s mineral wealth continues to attract international attention as countries seek to strengthen their access to critical materials.

At the heart of this competition is the need to establish more sustainable and diversified supply chains. Currently, China clearly dominates the refining and processing of these materials, transforming nearly 50% of critical minerals and controlling much of the global battery-grade materials supply. This imbalance has prompted countries like the U.S. and the European Union to ramp up efforts to diversify supply chains and reduce dependence on Chinese processing capabilities.

China’s Stronghold on Global Mineral Processing

China’s rise as the dominant supplier of transition minerals is the result of decades of strategic planning, technological advancements, and policy shifts. While the country’s industrialization initially revolved around coal, its government began prioritizing rare earth element (REE) mining in the 1970s. By the 1990s, China had already become the global leader in mineral refining, thanks to its rapid development of high-purity refining technologies.

However, it was during the 2000s that China fully recognized the strategic value of transition minerals, particularly in clean energy technologies. While coal, gold, and iron ore remained major exploration priorities, investments in minerals like copper, molybdenum, tin, and tungsten grew. As China intensified its push for new energy vehicles (NEVs), lithium, cobalt, and nickel gained importance. In 2009, the government launched the “Ten Cities, Thousand Vehicles” initiative, marking the industrialization of NEVs and cementing the need for these critical materials.

By 2014, China further reinforced its green energy ambitions with policies promoting EVs, renewable energy storage, and low-carbon technologies. With substantial policy support and subsidies, NEV production skyrocketed. The following year, the “Made in China 2025” plan prioritized key industries reliant on transition minerals, further solidifying China’s role in the global supply chain.

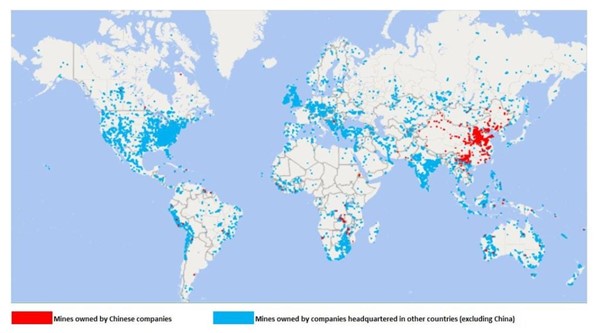

China’s role in global mineral ore production is relatively limited in most cases, with a few key exceptions. The longtime interest of China in acquiring a dominant presence in the market has indeed led Chinese companies to offset limited domestic ore reserves, actively expanding their mining operations abroad.

Chinese companies’ investments in both domestic and international mine projects

China dominates the extraction of natural graphite, rare earths, and silicon, accounting for at least 70% of global output in these categories. It has long maintained a strong presence in select resource-rich nations, such as Guinea for bauxite, the Democratic Republic of Congo for cobalt, and South Africa for platinum group metals. In recent years, China’s overseas reach has widened, with investments in bauxite and nickel extraction in Indonesia, lithium mining in Latin America and Zimbabwe, and various other projects worldwide.

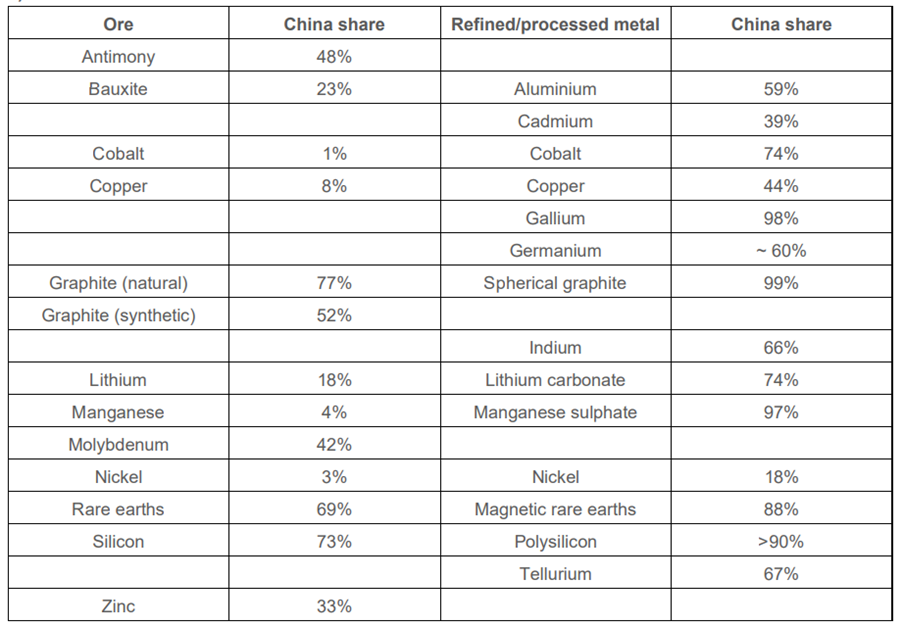

However, its influence is far more pronounced in the transition minerals’ refining and processing stages. China has cemented itself as the global leader in mineral refining, processing the majority of the world’s battery-grade materials. According to the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, it controls over 90% of global supply for key materials like gallium, graphite, and rare earth magnets, while refining over 60% of aluminium, cobalt, and lithium carbonate. This dominance enables China to dictate global supply and pricing, reinforcing its strategic influence.

China’s share of global ore and metal production for selected critical materials (data for 2022 & 2023)

China hosts a vast network of companies importing transition minerals and specializing in their refining, solidifying its dominance in the global supply chain. In lithium processing, Ganfeng Lithium Co., Ltd. is a key player, engaged across the entire lithium value chain, from mining to battery production. Tianqi Lithium Corporation also plays a significant role, with major stakes in Australian lithium mines and processing facilities in China.

For cobalt, China Molybdenum Co., Ltd. (CMOC) controls the Tenke Fungurume Mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo, a crucial global cobalt source. Zhejiang Huayou Cobalt Co., Ltd. refines cobalt and manufactures battery materials for the EV sector. In nickel, Tsingshan Holding Group leads global production, particularly through its large-scale Indonesian operations, while Jinchuan Group operates both domestically and in Africa. China also dominates rare earth processing, with China Northern Rare Earth Group and China Minmetals Rare Earth Co., Ltd., supplying essential materials for high-tech industries.

Also, several Chinese companies are heavily involved in extracting and processing minerals globally. China Nonferrous Metal Industry’s Foreign Engineering and Construction Co. Ltd. (NFC) operates the Chambishi Copper Smelter in Zambia, refining copper concentrates. China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) has expanded into nickel processing in Papua New Guinea. China Railway Group Limited (CREC) is developing a bauxite-alumina project in Guinea, which includes an alumina refinery.

Shifting the Balance: Strategies to Challenge China’s Lead

Such a great dominance of China on transition minerals proves its influence on global supply chains. Even if it does not control the majority of critical mineral ores, the fact that China maintains a leading position in refining and processing grants it significant leverage over international prices. Analysts from the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies underline that even minor shifts in its export volumes – whether deliberate or incidental – can disproportionately impact global markets. These price fluctuations, combined with short-term variations in global demand, create extreme volatility, especially for critical minerals, which are often traded in small, illiquid, and opaque markets.

Philip Andrews-Speed, Senior Research Fellow with OIES’ China Energy Research Programme, presents in particular the case of the Mountain Pass rare earth mine in California, which exemplifies the challenges posed by such instability. It has faced periodic shutdowns due to price swings and stringent environmental regulations. Only with financial backing from the U.S. Department of Defense was the mine able to construct its processing facility – before that, its ores were shipped to China for refining.

Several countries are strengthening their domestic industries to secure access and transformation of transition minerals. In April 2023, Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry introduced subsidies covering up to 50% of mine development and smelting costs for Japanese Rare Metals and Metalloids, targeting key minerals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, graphite, and rare earth elements, essential for EV batteries. Similarly, Canada took steps to protect its critical mineral resources by blocking the 2024 sale of rare earth element stockpiles to a Chinese buyer, instead ensuring they remained under Canadian ownership to support domestic supply chain resilience.

The U.S. and the European Union recognized their dependence on China for critical minerals and are taking steps to enhance supply chain resilience. Nevertheless, industrial policies are increasingly being used to boost domestic capabilities in the critical minerals supply chain.

In the U.S., measures such as the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) set requirements for EV battery mineral content to come from the U.S. or free trade partners, while restricting reliance on China. The U.S. also provided a 10% tax credit for mineral production and incentives for renewable energy components and critical mineral projects. In the U.S., Albemarle Corporation is a major lithium producer with refining operations in North Carolina and Nevada, as well as international facilities, supplying lithium hydroxide and carbonate for EV batteries. Arcadium Lithium specializes in lithium processing for high-performance battery applications and operates refining facilities in the U.S. and Argentina. MP Materials runs the Mountain Pass rare earths mine in California and is working to develop domestic refining and magnet production capabilities. Freeport-McMoRan is a leading copper producer with refining operations in Texas and Arizona, supplying essential materials for electrical wiring, renewable energy infrastructure, and battery technology.

In March 2024, the European Union introduced the European Critical Raw Materials Act, aiming to strengthen supply chains by investing across the value chain and setting domestic targets for extraction, processing, and recycling.

In Europe, Umicore, based in Belgium, refines cobalt and nickel for battery materials and operates advanced recycling facilities to recover valuable metals. Germany’s BASF is expanding its production of cathode active materials, crucial for lithium-ion batteries, with new plants in Germany and Finland. Norway’s Norsk Hydro specializes in refining and recycling aluminium, essential for lightweight EV components. Sweden’s Boliden processes copper and zinc at its smelters and refineries, supplying key materials for electrical wiring and battery technology while focusing on sustainable mining and metal recycling to support Europe’s transition to clean energy.

If these dynamics are reinforced, efforts to expand mining and processing capabilities outside of China are expected to make gradual progress in diversifying critical mineral supply chains, with increasing momentum over the next decade.

With a focus on improving predictability and maximizing profitability, INCONCRETO is an international consultancy, leveraging the high-level expertise of its partners, that is specialized in capital project optimization in the mining and refining sectors.

Our services include:

– Business Planning and Project Execution Planning to optimize resource use and operational efficiency.

– M&A Support, Due Diligence, and Auditing to assess and navigate mining investments

– Technology and Supply Chain improvements for the global mineral supply chain

For further readings, you may consult these sources:

- The Role of Critical Minerals in Clean Energy Transitions, by IEA

- A deep dive into China’s role as “critical mineral monolith”, by Mining Technology

- How world’s top CO2 emitter China became a major player in transition minerals and renewable energy, by Global Witness

- Why China’s critical mineral strategy goes beyond geopolitics, by WEF

- China’s global reach grows behind critical minerals, by S&P Global

- Power Playbook. Beijing’s Bid to Secure Overseas Transition Minerals, by AIDDATA

- Responding to the China challenge: Diversification and de-risking in new energy supply chains, by the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies

- Critical Thinking on Critical Minerals, by the Federation of American Scientists

- Critical Minerals: Western-led Efforts to Build Out the Critical Mineral Policy Framework for Secure Supply Chains, by Steptoe

Newsletter

© INCONCRETO. All rights reserved. Powered by AYM