INCONCRETO NEWS

The Vaccines’ Ecosystem in the MENA Region: Diversified Backgrounds and Multiple Challenges Ahead

Vaccination presents a critical challenge in the Middle East, as well as across the broader Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region.

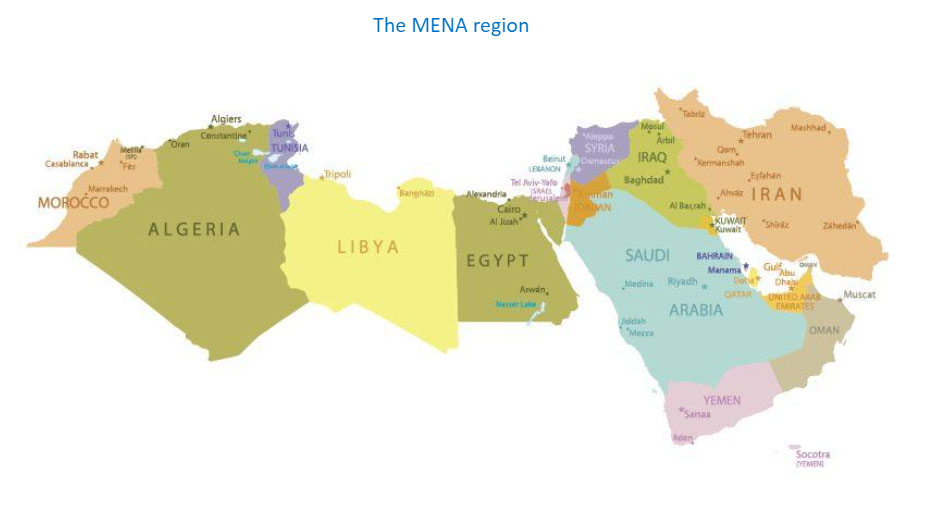

In this publication, our investigation will focus on this expansive region, which encompasses a diverse range of countries that span a vast geographical area and exhibit substantial disparities in terms of political systems, economic prosperity and living standards.

A shared aspect among these countries is the limited capacity for local vaccine manufacturing. However, it is feasible to classify them into distinct categories based on their varying degrees of access to vaccines from major international pharmaceutical companies operating within the global markets.

Based on this criterion, these are the three possible categories which we will consider for our understanding and analysis:

- The six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries: Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates (UAE). This group encompasses countries that generally encounter minimal obstacles when it comes to funding new vaccines or their vaccination initiatives. We will also include Israel here, in light of the prosperous economic conditions of this country.

- The three long-standing eligible countries to the support and assistance coming from Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance: Djibouti, Sudan, and Yemen, and since 2019 Syria. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance is an international organisation established with the mission to save lives, reduce poverty and protect the world against the threat of epidemics and pandemics, in particular in developing countries.

- The 10 non-Gavi countries – Algeria, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Palestine, and Tunisia. These nations encounter challenges stemming from the dynamics of the global vaccine market, restricted financial resources, limited negotiation leverage, and insufficient procurement mechanisms at the national level.

In this article, we will construct an overview of the primary strategies employed by these diverse countries in the procurement and distribution of vaccines. Our analysis will concentrate on the evolving approaches adopted both before and after the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020. These strategies aimed to address underlying challenges and to establish vaccination ambition targets with varying feasibility levels for the population’s protection against the virus.

Vaccines in the MENA region: a variety of procurement mechanisms

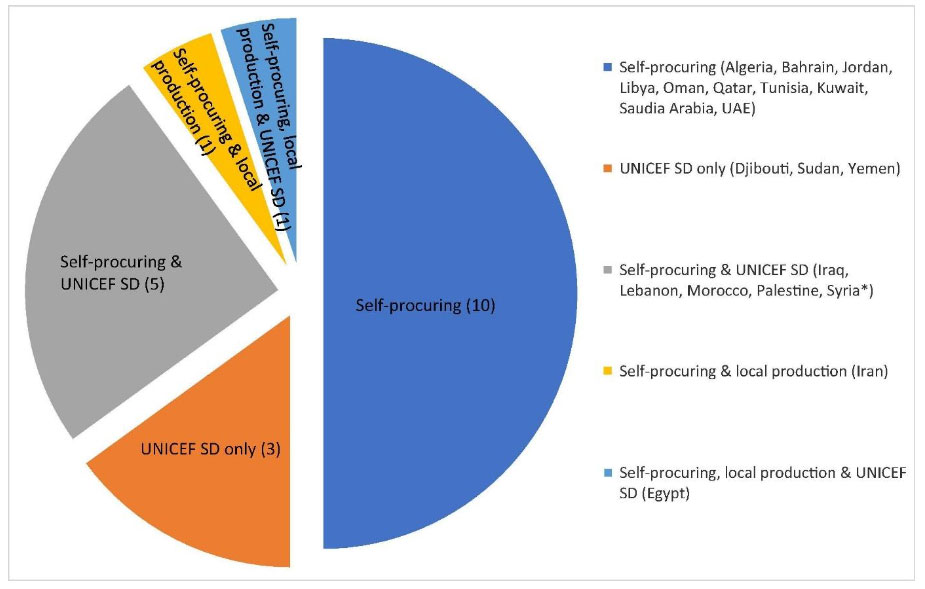

The MENA region has historically exhibited a variety of procurement mechanisms within the pharmaceutical industry, and these mechanisms significantly influence the effectiveness of vaccination programs. A comprehensive classification, established right before the Covid-19 pandemic and highlighting the key characteristics, was published by Elsevier.

The GCC countries procure vaccines either directly or through the GCC group purchasing mechanism, in this latter case particularly for vaccines that are part of their national immunization schedules. Using a group contracting model, the GCC purchasing program streamlines the tender and bidding process on behalf of its member countries and subsequently, each country independently enters into contracts with suppliers and manages payment arrangements.

In such configuration, the GCC program exclusively manages the initial stages of the procurement process, which include tendering, bidding, supplier selection, and adjudication. When suppliers engage with individual countries, they are obligated to provide consistent pricing across all six nations. This system allows for the advantages of group procurement, especially beneficial for smaller countries. However, each country remains responsible for funding its vaccine supply and deciding to what extent it will utilize this mechanism to meet its national vaccination program requirements. The competitiveness of prices secured by the GCC purchasing program is influenced by market size and preferences for new products and vaccines produced in industrialized nations.

Even if it is not part of the GCC programme, Israel, being economically independent on the international markets, is capable of ensuring a self-procuring approach for vaccines.

Countries receiving Gavi support are eligible for funding to acquire new and underused vaccines and have access to WHO pre-qualified products. Both Gavi-financed vaccines and conventional vaccines can be procured through UNICEF Supply Division (SD) at favourable prices.

At times, external aid provides financial support for conventional vaccines, whether partially or entirely. UNICEF SD provides an all-encompassing suite of services, including issuing requests for proposals and the communication of selection criteria and instructions. This strategy centralizes vaccine demand, sets pricing and volume objectives, evaluates manufacturer bids, and manages various aspects such as shipment logistics and payments. This approach enhances market efficiency, reducing transaction expenses and streamlining interactions between buyers and sellers.

While this procurement approach yields substantial benefits, experts highlight potential long-term drawbacks. These countries run the risk of missing out on opportunities to develop their capacity, exercise decision-making autonomy, and assert ownership. Indeed, governance challenges, instability, and conflicts in these nations have impeded progress and the attainment of target objectives, frequently disrupting the typical evolution of supply chains and rollout procedures.

Non-Gavi countries typically engage in self-procurement within the global market. Yet, the majority of them encounter obstacles in fulfilling their vaccine requirements, accessing a consistent supply of vaccines at reasonable prices, and grappling with the introduction of new vaccines recommended by organizations like the WHO and National Immunization Technical Advisory Groups (NITAGs).

Up until the onset of the pandemic, Iran, and to a lesser extent, Egypt and Tunisia, had a limited local production for a select number of traditional vaccines. Additionally, countries like Egypt, Morocco, Palestine, Lebanon, and Iraq utilized UNICEF SD for the procurement of certain vaccines. In some nations, central medical stores imported vaccines alongside other medical supplies, whereas in others Pasteur Institutes were, or continue to be, responsible for vaccine supply.

Here, the procurement system is frequently intricate, expensive, and lacking in transparency. Within the pharmaceutical sector, both public and private local entities often impose substantial fees and profit margins on local governments when it comes to vaccine imports. This practice is driven by the need to generate income to offset their ongoing expenses, resulting in an adverse impact on vaccine procurement efficiency. Furthermore, in numerous countries, public procurement processes, originally designed for different goods and pharmaceutical products, are applied to biological vaccine products without accounting for their unique specificities.

Regarding the primary vaccine suppliers within multinational corporations, in 2008, the MENA region witnessed the presence of five suppliers (GSK, Sanofi-Aventis, Merck, Wyeth, and Novartis) who collectively held an 85% share of the vaccine market in terms of value. By 2018, the global market was dominated by four manufacturers (Sanofi, GSK, Pfizer, and Merck), each enjoying quasi-monopolies for various newer vaccines such as Rotavirus Vaccines (RV), Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV), and Human papillomavirus (HPV).

Nonetheless, a limited cluster of vaccine manufacturers primarily situated in India, China, Brazil, and Indonesia are gradually assuming a significant role in supplying vaccines to these nations, encompassing both traditional and newer vaccine varieties.

It is relevant to observe that, alongside these challenges at the global level on vaccine procurement, some additional challenges arise from regional and local factors. One of the characteristics of vaccine demand in MENA is its fragmented nature. There is minimal visibility or predictability of vaccine demand at the regional or subregional levels except for the GCC countries where a certain consolidation of the demand is conducted.

Historical obstacles and opportunities for efficient vaccination roll-out in the MENA region

Beyond acquiring vaccines, another key challenge is rolling them out all over the territories in the MENA region, which implies numerous obstacles, but also a bunch of opportunities for ensuring its efficiency.

In our previous publication on the vaccines’ distribution in Africa, we emphasized the essential factors and infrastructure components necessary to ensure a comprehensive return on investment after acquiring vaccines from international producers. These very same crucial measures can be relevant, including for the Middle East and North Africa region. This applies particularly to effective vaccine logistics planning, distribution to remote areas (especially desert villages), and ensuring the proper management of the cold chain at all stages.

In this context, experts highlight the opportunity to leverage on the existing immunization programmes in the region, such as those implemented for diseases like polio and measles, which are currently ensured by specific vectors not only in the GCC countries, but also in all the others.

Through collaborative endeavours orchestrated by WHO and UNICEF, and leveraging the existing logistics infrastructure, the outbreak of polio in Syria in late 2022, which had the potential to spread to neighbouring regions, including Pakistan, was addressed. Promptly, the essential healthcare infrastructure had to be reinstated and restocked. This involved the redeployment of healthcare personnel to administer vaccines in the most heavily impacted areas and facilitating the transportation of vaccines across conflict zones whenever feasible.

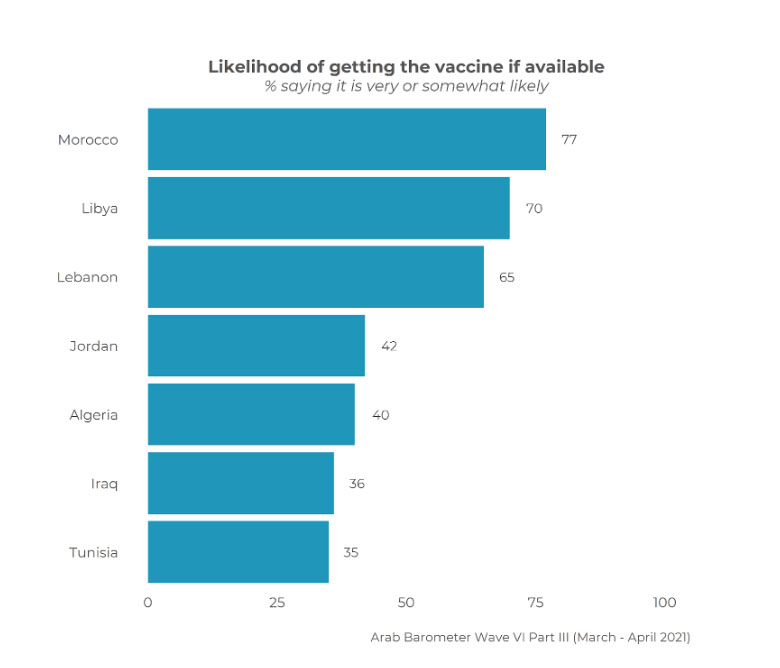

Another significant factor contributing to the slowing down of vaccine rollout in the MENA region is the widespread vaccination hesitancy. This reluctance towards vaccines, which is more prevalent here than in other regions of the world, is attributed primarily to historical and cultural resistance. A comprehensive analysis of the Muslim-specific influences should also be envisaged since it could provide deeper insights into the social and religious determinants of vaccine hesitancy in this area. Furthermore, vaccine hesitancy, which is unusually prevalent among highly educated individuals in society, is also linked to various instances of misinformation circulating among Middle Eastern and Muslim populations. Some of these narratives depict vaccines as part of a conspiracy to weaken Muslims or spread diseases to non-Western communities.

We observe in part this vaccines’ reluctancy in the rate of acceptance expressed for the potential Covid-19 vaccine when it had not been conceived and developed yet. Some countries displayed a very low interest:

Lastly, the persistent civil, political, and economic instability in numerous countries across the MENA region further exacerbates the noticeable disparities in vaccines distribution. These disparities gained international attention during the Covid-19 pandemic explosion when, as of August 2022, reports indicated that while the UAE and Qatar boasted vaccination coverage rates of 98% and 94%, only 1.5% of Yemenis had received the vaccine. The scarcity of vaccines gave rise to the term “vaccine apartheid”, underscoring the glaring inequities between countries that were successfully rolling out vaccines and those that were not.

Beyond the pandemic: bypassing vaccine diplomacy towards autonomous vaccines manufacturing?

The management of the Covid-19 pandemic in the MENA region followed two distinct approaches.

On one hand, the COVAX initiative played a pivotal role in ensuring innovative and equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines for all particularly in the poorest nations, regardless of their financial status, once these vaccines became available.

On the other hand, the GCC countries pursued a strategy of directly procuring vaccines from the international market and major pharmaceutical industry players. Within this framework, the UAE emerged as a robust hub in the region. Additionally, countries like Bahrain, Egypt, and Turkey diversified their sources by procuring vaccines from Moscow, Beijing, and not just from the United States.

This phenomenon is often referred to as “vaccine diplomacy”, where countries like Russia and China sought to expand their influence in the Middle East by striking significant vaccine deals, often accompanied by substantial commercial investments in various sectors. This vaccine diplomacy is just one aspect of a broader strategy aimed at reshaping the geopolitical dynamics in the region.

Despite these significant international relations established in recent years, it’s noteworthy that the Covid-19 pandemic has provided an opportune moment for the wealthier countries in the MENA region to initiate international agreements with both prominent Western and Eastern pharmaceutical companies. These agreements are aimed at establishing and scaling up local vaccine manufacturing capabilities. In our forthcoming publications, we will delve deeper into these forward-thinking and innovative projects.

INCONCRETO, as an international consultancy, can provide expertise in capital project optimization and oversee critical paths for biopharmaceutical project execution.

Connect with our team!

We combine technical expertise with large program execution practices, improving predictable outcomes and steering profitability on Capex/Opex project investments.

For further readings, you may consult these sources:

- Vaccine procurement in the Middle East and North Africa region: Challenges and ways of improving program efficiency and fiscal space, published by Elsevier

- WHO update on polio outbreak in Middle East, by the WHO

- Assessing vaccine hesitancy in Arab countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region: a scoping review protocol, published by BMJ Open

- Vaccine Access and Distribution in MENA, by the Tahir Institute

- How the Covid vaccine rollout exposed inequality in the Middle East, by Middle East Eye

- Vaccine Diplomacy: In 2021, the UAE will become the new vaccine hub of the Middle East, by Observer Research Foundation

- Russia, China expanding Middle East sway with COVID-19 vaccines, by Aljazeera

Newsletter

© INCONCRETO. All rights reserved. Powered by AYM